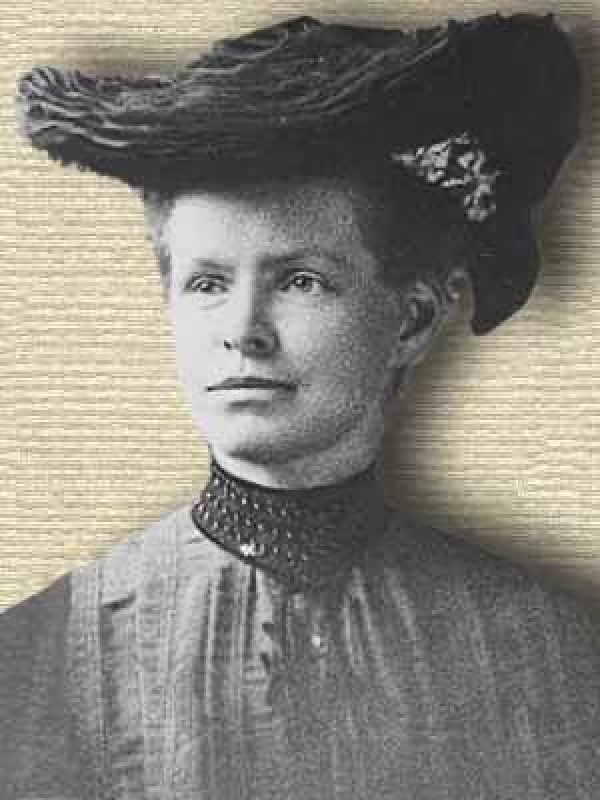

- Birth Name: Nettie Maria Stevens

- Born: July 7, 1861, Cavendish (Vermont)

- Died: May 4, 1912 (50 years old), Baltimore

- Nationality: USA

Fighting for the right to research

Nettie Stevens was not only a brilliant biologist: she was also a woman who, at the beginning of the 20th century, had to fight for the right to do science. At a time when universities barely admitted women and laboratories were closed to them, she managed to get a PhD and make a place for herself in the world of research. Her determination was a first act of defiance against the system.

1905: The discovery that changes everything

By studying mealworms, she made a fundamental observation: she demonstrated that biological sex is determined by chromosomes. More precisely, it is the Y chromosome, transmitted by the father, that gives birth to a male individual. This result would lay the foundations of modern genetics.

"It's not just a matter between two scientists, it's a reflection of a sexist system."

Erasure: a mechanism, not an accident

Despite the importance of her discovery, her name quickly disappeared from memories. Thomas Hunt Morgan, a much more influential researcher, took up her ideas, integrated them into his own work, and ended up receiving the Nobel Prize in 1933. Nettie Stevens was never rewarded.

It would be easy to say that Morgan "stole" the discovery, but the reality is more complex. The problem is not so much Morgan as the system around him.

The patriarchal system at work

At the time, women in science were systematically invisibilized. They were considered, at best, as assistants. Their work was little published, rarely cited, and they were excluded from positions of responsibility.

Nettie Stevens is therefore a striking example of what is now called the Matilda effect: when the work of a woman is attributed to a man, not out of direct malice by a single individual, but because the system in which they evolve is deeply biased.

She died at 50, without knowing that her discoveries would change science. Today, her journey reminds us that in a patriarchal world, genius is not enough.